The nearsighted

Ray Bradbury had a deep concern for the welfare and destiny of his fellow humans. Through his stories and in his life, he imagined ways to create a better world and offered cautions designed to sustain the one we have. He had no scientific or technical training, but he had an innate sense of what might come in the future—miraculous devices that, at the time, were just science fiction.

He once described the kind of fiction he wrote as “really sociological studies of the future, things that the writer believes are going to happen by putting two and two together . . .” His remarkable descriptions of future devices stayed with readers across generations, and his words always come to mind whenever such devices become reality. Can you guess which advances he envisioned in the following passages?

Bradbury’s worlds

of tomorrow

“There Will Come Soft Rains,” first published in Collier’s magazine, May 6, 1950

“The Veldt,” originally appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, September 23, 1950

“The Murderer,” was included in The Golden Apples of the Sun, 1953

Fahrenheit 451, 1953

“. . . he had visited the bank, which was open all night every night with robot tellers in attendance.”

Bradbury’s interplanetary influence

The writer’s ability to see the future, especially beyond Earth’s thin and fragile layer of atmosphere, attracted the attention of astronauts and scientists, who became some of his most dedicated fans during his lifetime—fans who shared his dreams and took Bradbury’s influence to places that reached beyond even his vibrant imagination.

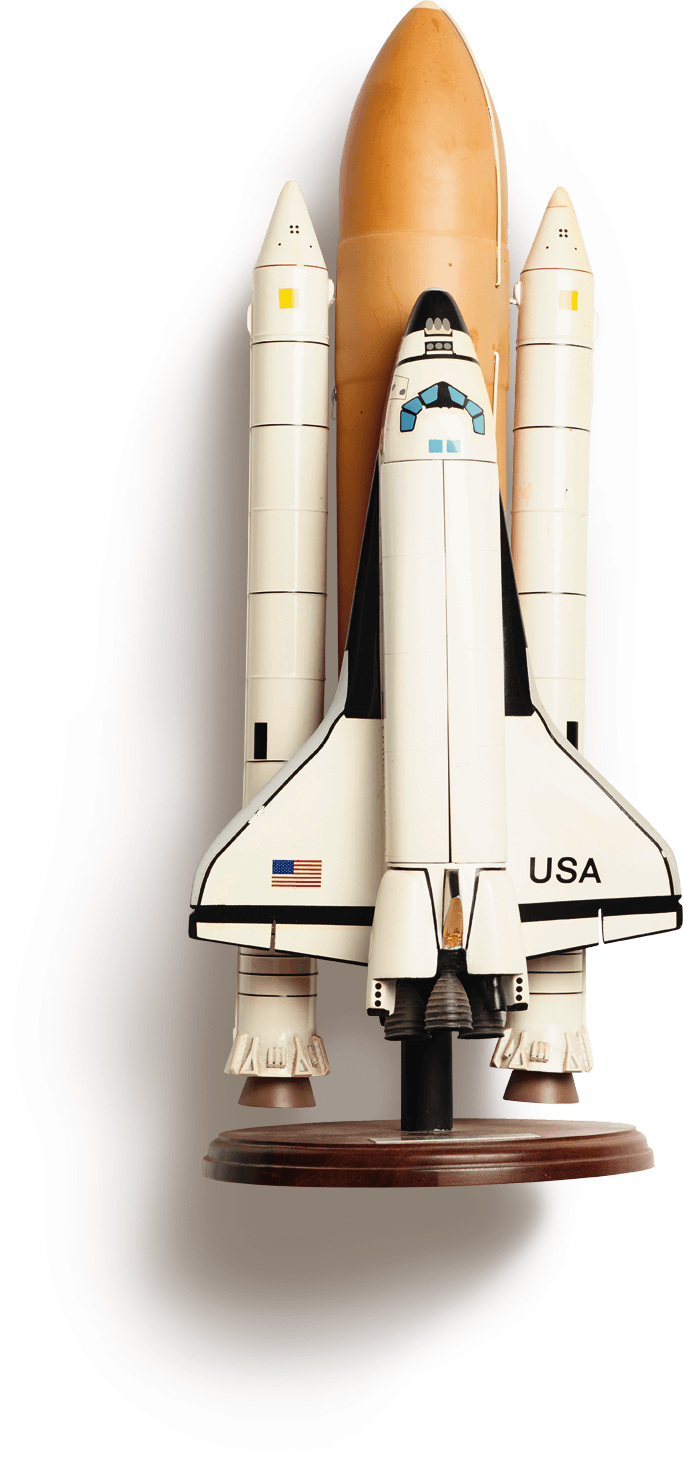

During the 1960s, he became a frequent speaker at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, and his award-winning articles on the Gemini and Apollo missions for Life magazine were read by millions.

Later, as the space program began to focus on unmanned interplanetary exploration, Bradbury participated in the “Mars and the Mind of Man” panel discussions with astronomer Carl Sagan and the JPL teams involved with the Mariner 9 orbital photographic surveys of Mars; he was in the mission control room with NASA’s Wernher von Braun when Mariner 9 achieved Martian orbit in 1971, and again for the Viking Mars landings in 1976; Bradbury joined scientific panels at JPL for the Voyager close approach missions to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; and he was honored by team members of the Mars Odyssey thermal imaging program and the most enduring Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity.

His abiding presence in the aerospace community led to friendships with astronauts Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin (Apollo 11), Alan Bean (Apollo 12), Walt Cunningham (Apollo 7), David Scott (Apollo 15), and Harrison Schmidt (Apollo 17), as well as such Space-Age luminaries as writer Arthur C. Clarke, astronomer Carl Sagan, and JPL director Bruce Murray.

In 1979, Bradbury hosted and cowrote an ABC news special on space exploration, “Infinite Horizons: Space Beyond Apollo,” for which he won an Emmy Award from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

Decades later, in 2007, a digital copy of his novel The Martian Chronicles would make its own journey into space to the Red Planet, transported by the Phoenix Mars Lander. And on August 22, 2012, just ten weeks after Ray’s death, the rover Curiosity’s touchdown point on Mars was renamed “Bradbury Landing.” He also has an asteroid, a moon crater, and Martian terrain features named in his honor. Who knows where Bradbury’s name or works will appear next? As new generations of readers discover his words, they can see there will be more tributes to come.

“The least scientific person you’ll ever meet”

What’s surprising is that while the scientific community embraced him, Bradbury knew his limitations. “I’m probably the least scientific person you’ll ever meet,” he once said in a TV interview. And, on occasion, even the youngest of readers would point this out.

‘A nine-year-old boy came up to me in a bookstore the other day and said, “Mr. Bradbury,” I said, “Yes.” He said, “You know that book of yours, the Martian Chronicles?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Page 92, we have the moons of Mars rise in the east.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “No.” So I gave him 10 bucks to shut him up.’

He believed that if you could imagine it, it could be done, even though he prized older technology over the new: Bradbury preferred bicycles to cars, typewriters to computers, and handwritten letters to emails. Yet this inclination did not prevent him from making a massive contribution to global technological advancement while always reminding us of this important lesson: It’s only advancement if it enhances our humanity.

Think like Bradbury

Of course, the writer’s most valuable contributions to humanity are the questions his work raised. To think like Bradbury is to dream and to be aware of possibilities—the good, the bad, and the unknown. Ponder these as you confront each day:

- What lies ahead and how can we best prepare for it?

- Which socially unhelpful innovations he foresaw decades ago could be reversed or how could they be changed?

- How can we protect the freedom of the imagination?

- How can we all start believing that anything is possible?

"I was not predicting the future, I was trying to prevent it."

– R.B.