An hour’s writing

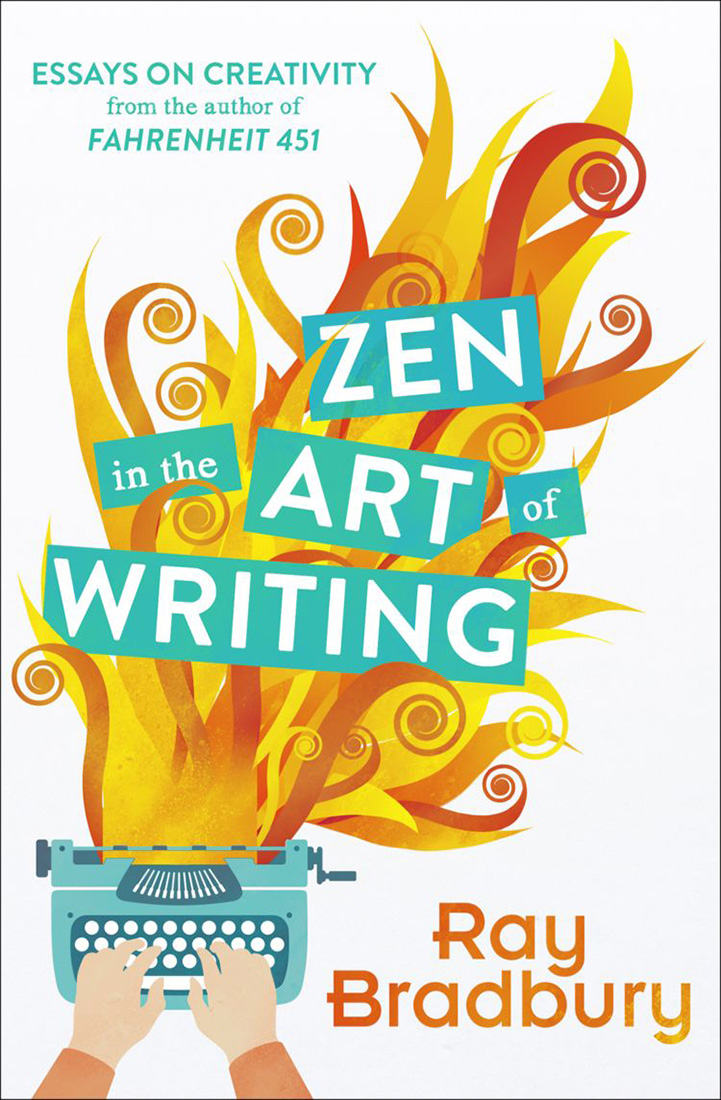

Bradbury advocated a daily dose of writing as a cure against the ills and sorrows of everyday life, a tonic that has the potential to energize all that we experience. In the articles collected for his 1990 book Zen in the Art of Writing, and in lectures given throughout his life, he shared the beneficial power of the written word. For the act of writing need not be treated as a chore, nor should it be the domain of only a chosen group.

Read on—and write away—with Bradbury’s voice as your guide. May his insights into the value of writing carry you through a sentence, a paragraph, and perhaps even a short story, but, more important, on through your life beyond the page.

Zen in the Art of Writing — excerpt from Preface

What, you ask, does writing teach us?

First and foremost, it reminds us that we are alive and that it is a gift and a privilege, not a right. We must earn life once it has been awarded us. Life asks for rewards back because it has favored us with animation.

So while our art cannot, as we wish it could, save us from wars, privation, envy, greed, old age, or death, it can revitalize us amidst it all.

Secondly, writing is survival. Any art, any good work, of course, is that.

Not to write, for many of us, is to die.

We must take arms each and every day, perhaps knowing that the battle cannot be entirely won, but fight we must, if only a gentle bout. The smallest effort to win means, at the end of each day, a sort of victory. Remember that pianist who said that if he did not practice every day he would know, if he did not practice for two days, the critics would know, after three days, his audiences would know.

A variation of this is true for writers. Not that your style, whatever that is, would melt out of shape in those few days. But what would happen is that the world would catch up with and try to sicken you.

If you did not write every day, the poisons would accumulate and you would begin to die, or act crazy, or both.

For writing allows just the proper recipes of truth, life, reality as you are able to eat, drink, and digest without hyperventilating and flopping like a dead fish in your bed.

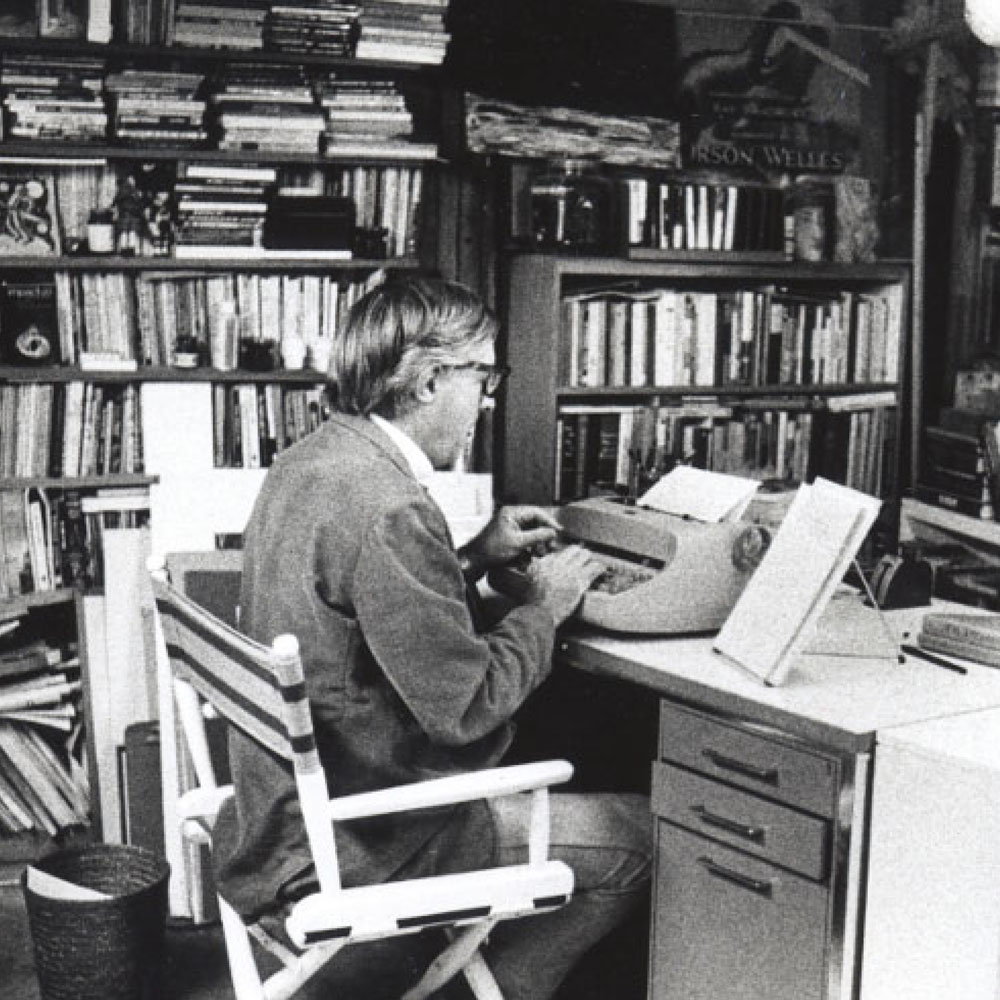

I have learned, on my journeys, that if I let a day go by without writing, I grow uneasy. Two days and I am in tremor. Three and I suspect lunacy. Four and I might as well be a hog, suffering the flux in a wallow. An hour’s writing is tonic. I’m on my feet, running in circles, and yelling for a clean pair of spats.

So that, in one way or another, is what this book is all about. Taking your pinch of arsenic every morn so you can survive to sunset. Another pinch at sunset so that you can more-than-survive until dawn . . .

Now, it’s your turn.

Let there be words, many of them!

I believe that eventually quantity will make for quality. . . . Quantity gives experience. From experience alone can quality come.

Bradbury, the man of many words, stories, books and ideas offers some inspirational and practical advice to jump-start your daily writing practice. Here’s some of Ray’s tips interpreted by Colin Marshall on openculture.com

Start short. Don’t start out writing novels—they take too long—“write a hell of a lot of short stories,” he said. Give yourself time to improve; with each week and month, you’ll see your stories improve. He claims that it simply isn’t possible to write 52 bad short stories in a row.

Just type any old thing that comes into your head. He recommended “word association” to break down any creative blockages, since “you don’t know what’s in you until you test it.”

List ten things you love, and ten things you hate. Then write about the former, and “kill” the later—also by writing about them. Do the same with your fears.

Live in the library. Step away from your computer and expose yourself to new books often. There are numerous worlds to discover beyond your screen.

Writing is not a serious business.

Write with joy. If a story starts to feel like work, scrap it and start one that doesn’t.

Examine “quality” short stories. He suggested reading works by Roald Dahl, Guy de Maupassant, Nigel Kneale, and John Collier. Turn to stories with metaphors; surprisingly he considered New Yorker stories of late lacking in this department!

Read—a lot—but select wisely. Bradbury’s recommended well-rounded bedtime reading: one short story, one poem (especially Pope, Shakespeare, and Frost), and one essay. Of course, not just any essays. They should come from a diversity of fields, including archaeology, zoology, biology, philosophy, politics, and literature.

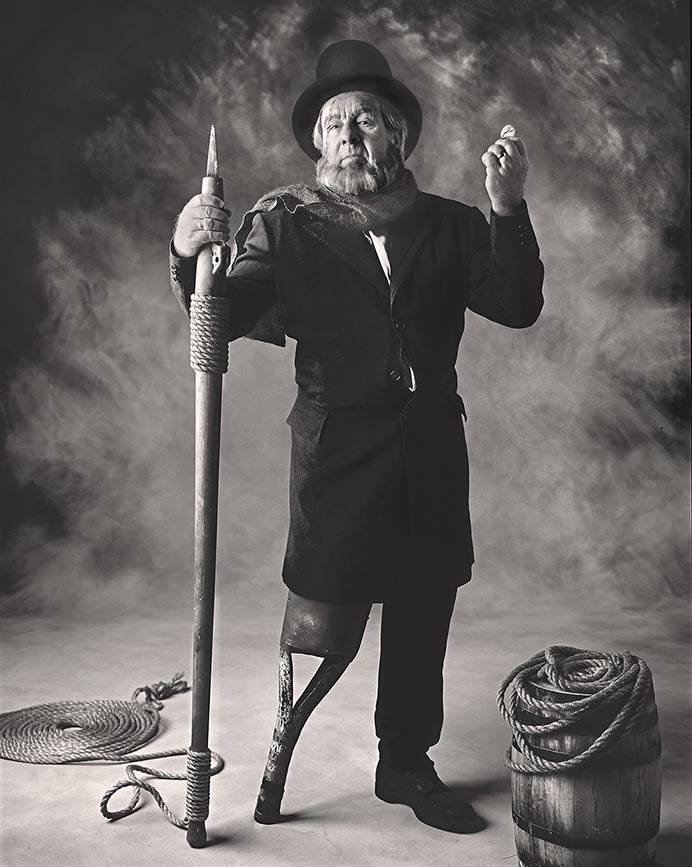

© 1986 Tom Zimberoff

© 1986 Tom Zimberoff

Do not . . . turn away from what you are—the material within you which makes you individual, and therefore indispensable to others.

Learn from the greats, but be you. Learn from your favorite writers, versus imitating them. Bradbury also initially imitated H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, and L. Frank Baum before developing his own unique style.

Fall in love with movies. Preferably old ones.

Develop a strong support system. Do you have friends who make fun of your writerly ambitions? Bradbury’s advice: “Fire them” without delay.

The goal is just one person to come up and tell you, “I love you for what you do.” Or, failing that, you’re looking for someone to come up and tell you, “You’re not nuts like people say.”